A study links Florida's "stand your ground" law with an increase in the homicide rate. In this 150-second analysis, ����ֱ�� clinical reviewer F. Perry Wilson, MD, examines the data and asks whether physicians have a duty to speak out.

I've been thinking quite a bit recently on whether physicians have a responsibility to speak out on issues that might be considered political. It's a tough line to walk, but my belief has always been that data is non-partisan. So this week, we wade into the controversial waters of so-called "stand your ground" laws, which provide immunity from criminal, and in some cases civil prosecution if an individual uses deadly force when they feel their life, or in some cases property, is threatened. Do these laws bear on the public health? If so, must we take a stand on them?

This paper appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine, suggests that, indeed, these laws are affecting people's lives.

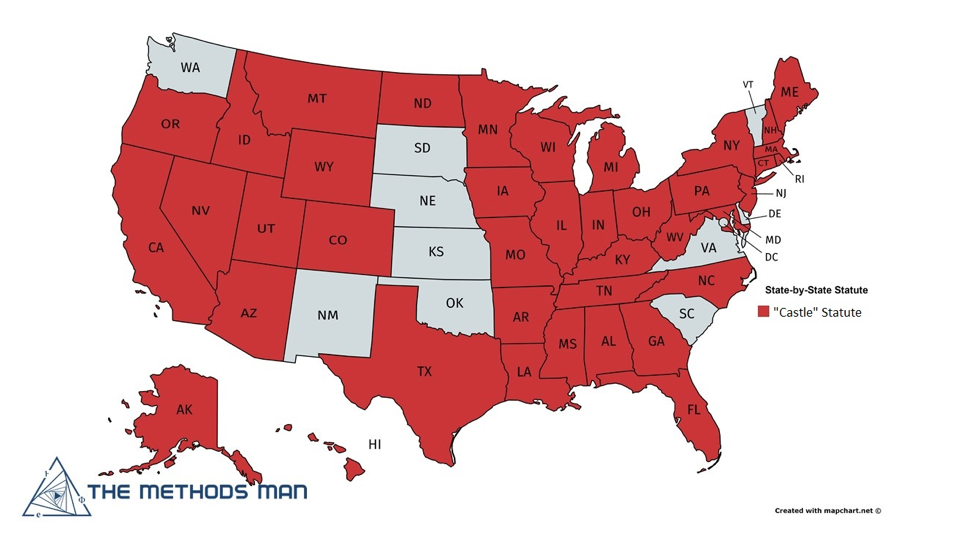

First some background. From the earliest founding of our country, the concept of "duty to retreat" predominated. Essentially, this doctrine suggests that one must make a reasonable effort to avoid conflict before resorting to force. But the "castle doctrine," which states that there is not necessarily a duty to retreat when one is threatened in his or her home, is pretty ubiquitous, as you can see.

First some background. From the earliest founding of our country, the concept of "duty to retreat" predominated. Essentially, this doctrine suggests that one must make a reasonable effort to avoid conflict before resorting to force. But the "castle doctrine," which states that there is not necessarily a duty to retreat when one is threatened in his or her home, is pretty ubiquitous, as you can see.

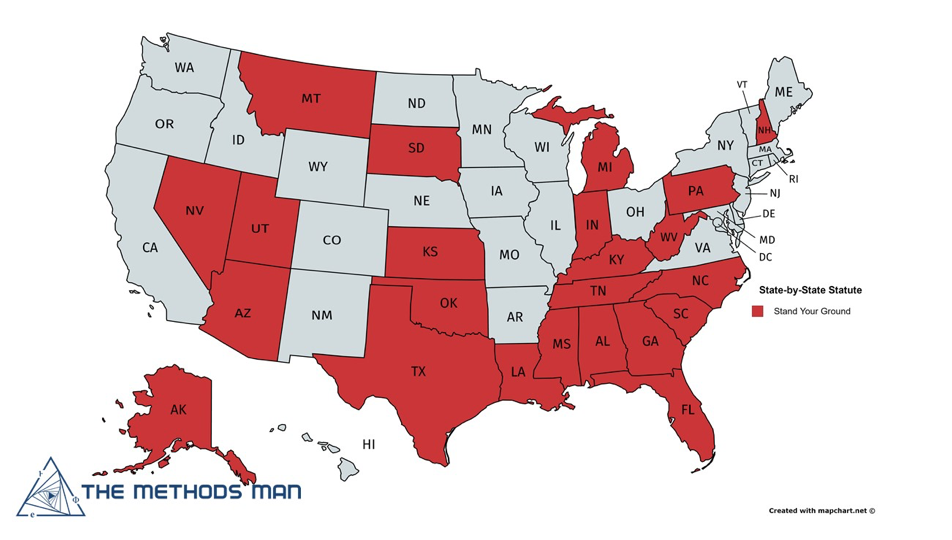

Stand-your-ground laws, though they differ state-to-state, usually remove the requirement to retreat when one feels threatened, even outside the home. As you can see, fewer states have adopted these laws, but they are becoming increasingly common.

Florida's stand-your-ground statute was adopted in 2005, and is pretty strong. It provides immunity from prosecution if an individual uses deadly force after feeling threatened, even in a public place. It allows the use of deadly force to protect property, such as during vehicle theft, and it protects the individuals using deadly force even when they instigate the confrontation.

Researchers wanted to determine how this law might affect homicide rates. One could imagine it would act as a strong deterrent for criminals. Conversely, perhaps the increased protections around the use of deadly force would lead to more use of deadly force.

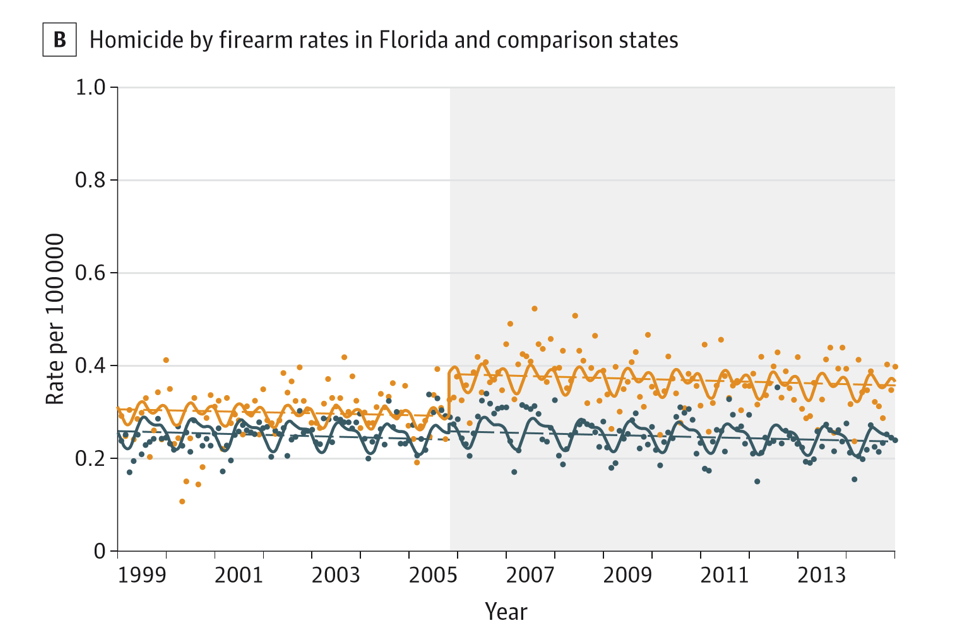

To figure it out, the researchers used what is called an interrupted time-series design. Simply put, you model the trend in homicide rates both before and after the law was enacted. This is a bit tricky, as you need to account for the overall decrease in homicide rates over time as well as seasonal factors. But what they found was fairly compelling.

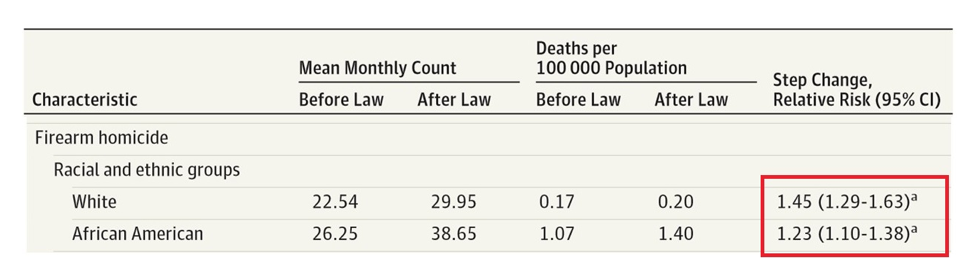

After the introduction of the stand-your-ground law, there was a sharp increase in the homicide-by-firearm rate, in yellow. Contrast that with the stable suicide rate in blue. Suicides tend to increase in times of social and economic strife, so that serves as a relatively decent control.

Also note the disproportionate negative impact on white versus African-American individuals, making this one of the only times I can remember seeing a law with a racial disparity that adversely affects the majority.

Of course, the most compelling issue is what is missing from these numbers. We don't really know who was killed here – the "victim" or the "perpetrator." We don't know if overall crimes went down even as homicides went up. And of course, we don't know whether these effects are unique to Florida, though I should say that other studies in other states found similar results.

So as clinicians, do we have a responsibility to speak out here? If we believe the results, that a law increases deaths, I would argue that we should. Speaking personally, I will. But this wasn't a randomized trial – we'll never get one of those – so there is room for those of all inclinations to maintain your political beliefs without violating your Hippocratic oath.

, is an assistant professor of medicine at the Yale School of Medicine. He earned his BA from Harvard University, graduating with honors with a degree in biochemistry. He then attended Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City. From there he moved to Philadelphia to complete his internal medicine residency and nephrology fellowship at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. During his post graduate years, he also obtained a Master of Science in Clinical Epidemiology from the University of Pennsylvania. He is an accomplished author of many scientific articles and holds several NIH grants. He is a ����ֱ�� reviewer, and in addition to his video analyses, he authors a blog, . You can follow .